The TMC History Project is a living document: the College encourages anyone with information, photographs, documents or artifacts relevant to the growth of our knowledge on the subject to email the TMC webmaster. More ...

"I have written on the history of Marshall College and was honored to know several of the college's founders. I believe strongly in Lumumba-Zapata College's vision of social justice, history, and activism and was eager to reshape the new DOC curriculum so that the original vision might be made meaningful for students in the 21st century."

— Dr. Jorge Mariscal, Professor of Literature

Brown-eyed Children of the Sun:

Lessons from the Chicano Movement, 1965-1975

By George MariscalChapter Six

"to demand that the university work for our people"

For the twentieth anniversary of “Third College” I provided a statement of my reflections on the formative years of the college. Consequently, I will focus this statement on a question that is frequently asked: “Given the goals articulated for the college in 1969 by students and the plan approved by the UC Regents in 1970, is Marshall College a success?” With one critical exception, the answer is “definitely yes.”

The one exception is the goal of a substantially increased presence of African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Native Americans within the student body and the faculty. At best, little progress has been made in both areas. However, this failure and lack of progress rest mainly, if not exclusively, with the broader campus and the academic departments.

By any of the measures for evaluating colleges at UCSD, Marshall College is both a resounding success and contributor to the excellence of UCSD. It has a diverse student body of almost 4,000 students and an excellent graduation rate. If it were a separate UC campus, its six year graduation rate in 2009 would be tied for fourth, just behind Berkeley, UCLA, and UCSD. Many of the academic programs proposed in the plan approved by the Regents continue today as either campuswide academic majors or departments. The college played a central role in the establishment and development of the Preuss Charter School, which has brought special national recognition and accolades to UCSD.

Although it can be very engaging to review the past and assess accomplishments and short comings, it is considerably more productive to focus on current challenges and undertake new initiatives to educate and inspire students. In doing so, it is to be hoped that the college’s history and past achievements will inspire and motivate Marshall College to continue its commitment to greater racial justice and equality while heeding the counsel of Martin Luther King:

“Our very survival depends on our ability to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant and to face the challenge of change.”

Dr. Joseph Watson was Provost of Third College, 1970-1981

During your years (1981-88) as Provost of Third College, what were the challenges to the college with respect to the college’s academic and cultural mission along with the activist philosophy specific to the college?

Dr. Joseph Watson preceded me as Provost of Third College and it was my fortune that the staff was already in place. It took me awhile to understand the undergraduate structure and the roles that committees and individuals had in the development and continued growth of the colleges. In my early times there was not a clear academic program reflecting the mission of the college nor did this occur until years later. The activist philosophy which had been so robust had begun to lose some of its spirit but new student leaders brought new thinking and also diverse enthusiasm in their college leadership but did not forget the early struggles of the creation of the college; One of those struggles was agreeing on a name for the college-a process which has faced other colleges and institutions.

When you reflect on the tumultuous beginnings of Third College and the initial radical concept behind Third College, what was gained and what was lost in the machinery of history?

The mention of Third College in the greater community and also in the university itself sparked expressions of derision. Though this college experienced a turbulent beginning it gave rise to a strong class of students but the underlined desire to create an ethnically diverse college was not altogether successful. UCSD is not considered by potential applicants and students as a friendly university. At Third College the minority students sought to find soul mates but in some ways this was also disappointing because they sought a broader base to meet their social needs as well as academic opportunities. Enriching diversity and culture inclusiveness is not a responsibility of one college but of the entire campus, reaching that point will indeed be a call to all student applicants.

Enriching diversity and cultural inclusiveness have been a tough goal for this campus over the decades. What are the hurdles we face and why do several people on campus expect Marshall College to lead in this cause?

I remember with pleasure the enthusiastic desire of the students to broaden the diversity of the university on various levels and expand academic offerings. The objectives were not only to enhance their own knowledge but also to increase the diversity of the student body and faculty.

It is gratifying to know and witness that some of these leaders of that earlier period have consistently continued their quests and inspired students in other educational settings to initiate activities which go beyond the traditional university recruitment programs.

What is a special initiative that helped the students during your tenure?

One of the more successful mentor-tutoring programs was initiated by Manuelita Brown in the field of mathematics. Within a short time these classes became extremely popular, it was the student academic support program which strengthened the students desire to achieve greater expertise in math while losing their fear of the subject.

Dr. Faustina Solis was Provost of Third College, 1981-1988

While many cities in America burned during the anguish that was the 1960s, the newest campus in the University of California System founded Third College. It was the hope then as now that faculty, students, and staff would join together to form a college that would lead higher education in realizing the best aspirations of the American Civil Rights Movement. Over the years since its founding, the leadership at Third College (now renamed, Thurgood Marshall College) have accepted the challenge to renew and advance the founding principles of Third College.

Thurgood Marshall College Provosts, over the years, have sought to institutionalize those aspirations by embedding their aims in academic programs. This is most evident in the academic programs that had their origins at the College. The Teacher Education Program, begun at Third College under the leadership of Professor Bud Mehan, has since established itself as an independent department offering degree programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Their focus remains to influence the quality and quantity of new teachers and scholars addressing issues of school and educational reform. The Communication Department began its existence as a program at Third College and is presently a full spectrum academic department with 30+ plus faculty with over 1000 majors. Very much of the same is true for the history of the Urban Studies and Planning Program, and the Ethnic Studies Department at UCSD.

Rafael Hernandez and Ashanti Houston-Hands served as TMC Deans of Students from 1991-99 and 2000-08 respectively. During this period, Hernandez initiated the Partner-At-Learning Program, or PAL, which offers academic credit to students for training and placement in local schools as tutors and mentors. The beginning of PAL coincided with the push led by Thurgood Marshall College faculty, students, and staff to open a charter school on campus serving secondary school students from low income backgrounds. That college-prep school, Preuss School UCSD ![]() , opened its doors to the children and families of Southeast San Diego fall 1999 with PAL tutors and mentors as part of the educational program. Since then, Preuss School UCSD has sent hundreds of graduates to the finest colleges and universities in the nation.

, opened its doors to the children and families of Southeast San Diego fall 1999 with PAL tutors and mentors as part of the educational program. Since then, Preuss School UCSD has sent hundreds of graduates to the finest colleges and universities in the nation.

Preuss School has also inspired UCSD to open a second secondary school, Gompers Preparatory Academy (GPA), in the Southeast San Diego community of Chollas View. GPA is also a college-prep charter school serving nearly 1000 youngsters grades 6-12. These two schools begun and inspired by Thurgood Marshall College have led other universities to follow suit. To date, university-sponsored college-prep charter schools serving underrepresented communities exists on 32 campuses of higher learning including UC Berkeley, UC Davis, UC Los Angeles, Penn, University of Chicago, Harvard University, Bard College, and many others.

But inspiration, like charity, begins at home. During the years that I was privileged to serve as Provost of Thurgood Marshall College, it was always my view that the topics students and faculty studied, debated, and learn in the three-quarter Dimensions of Culture (DOC) sequence would empower future graduates and leaders to learn to see themselves as productive actors in the grand, but imperfect, democracy of our country. Studying our diversity and our system of legal advocacy would encourage Thurgood Marshall College graduates to take their place in their communities of the future to renew and advance into the future the ideas and principles that brought this college into existence forty years ago.

Professor Cecil Lytle was Provost of Third/Thurgood Marshall College, 1988-2005

There are many wonderful myths about Third College/Thurgood Marshall College. In some ways, these myths hold more truth than false thinking. The college is often the eye of the hurricane with respect to campus tensions on social justice, race relations, and so called “culture wars”. The inception of Third College over forty years ago brought many conflicting expectations about a radical University of California college during the waning days of the Vietnam War and the turbulent 1960s. In our colorful history, we have figures such as Herbert Marcuse, Angela Davis and Carlos Blanco-Aguinaga. There has been an ebb and flow of invention and reconsideration. Clearly, the evolution of Third College touched countless students, staff and faculty beyond simple description. The college launched an amazing range of academic departments and programs over four decades. It takes a great stretch of the imagination to envision the impossible made possible. The provocative creation of the Preuss Charter School on campus over a decade ago has a proud path which leads back to the college. Moreover, the college writing program known as DOC (Dimensions of Culture) is often the lightning rod for passionate campus debate and activism. Political rhetoric usually rains hard in our part of the university map. In short, it all comes down to meteorology. We weather the storm. And we celebrate calm weather.

The significance of our college’s identity and role at UCSD takes on a renaissance feel. We continue to experience a rebirthing and a manifold sense of expression. The college has a powerful social vision but equally important is our respect for the sciences on campus. The sciences need the humanities and the reverse is equally true. The college believes each student has outstanding abilities in many realms. Thurgood Marshall College expects each student to excel in scholarly tasks and also societal roles. There is no contradiction here. The splendid life of Justice Thurgood Marshall demonstrates fully the integrity of this idea. Hard work and dedication accompanies the notion. It is a worthy ideal given the wholeness of forty years of spectacular campus history. There will be more myths to come about the college as these elusive myths turn into more steady legends.

Appointed in 2006, Professor Allan Havis is the current Provost of Thurgood Marshall College

In reflecting on celebrating forty years of academic services to our students, certainly the faces of our students and staff have changed, but our central mission has not.

TMC academic counselors and staff are unfailingly dedicated to upholding the college philosophy of developing the student as “scholar and citizen.” Academic Advising is a team of student advocates who encourage, respect, inspire and aid students in establishing and achieving their academic goals and objectives. First and foremost, it is charged with providing its students with sound academic guidance and challenging students intellectually and creatively—stimulating an attitude of academic confidence.

Central to our mission is an unwavering commitment to honoring student diversity and the exploration of diverse academic opportunities. An essential part of Academic Advising involves orienting students to the university, creating an environment supportive of the learning process, and championing the individual student’s effort in creating an educational experience congruent with their educational and life aspirations.

We strive to develop the respectful student who is passionate about learning and sharing their gained knowledge through active university and public service. We engender students who are courageous in their convictions and who seek to be positive contributing members of society.

We promote students’ growth by emphasizing the importance of involvement in college and campus organizations and leadership development. We encourage students to share their talents and knowledge in a manner that benefits all communities—locally and globally.

TMC Academic Advising, as it has over the years, contributes actively and creatively to the structure, development and implementation of a multitude of academic programs most recently in Dimensions of Culture, African-American Studies, Public Service and many general education options to serve our students’ educational growth and support our College’s mission. We work energetically with the College provost and faculty as well as administrators of the University.

We uphold the University’s policies and standards so our students know that regardless of the years that pass, the degree they earn always has the rights, privileges bestowed by the Regents of the University of California and its accompanying prestige.

We have the honor of serving the most awe-inspiring and accomplished of University students. Some things never change – not even in 40 years.

Former Academic Advisors

|

||

| Mike Kane | Cathy Baez | Yoly Woo-Hoogenstyn |

Mae Brown was Director of Academic Advising from 1979 - 1995 at which time she became Assistant Vice Chancellor & Director

of UCSD Admissions.

TMC Academic Advising Staff - May 2010

Living and Loving the Marshall Legacy

| Karen Correa-Fowler, Gretchen Hills, Gene Sandan, Emily Gonzales Assistant Dean |

| Stephanie Muldrow, Anne Porter, Denise Odom, Dan Landrum Dean |

Anne Porter has been the Dean of Academic Advising at Thurgood Marshall College from 1995 to present.

When I started teaching at UCSD in 1981, “communication” was an undergraduate program affiliated with Third College and not a full-fledged department as it would become a few years later. All faculty in the Communication Program were automatically Third College faculty. My affiliation with Third College was not something I ever had to think about; it was not something I ever regretted, either. As I write this, my daughter has just transferred to UCSD – Thurgood Marshall College. I could not be more pleased and proud.

My most intense involvement with TMC came when Cecil Lytle, newly the provost, asked me to chair a faculty committee to plan a new writing course to replace the Third College Writing Program as it had existed under the excellent leadership of Charles Cooper. Writing instruction was first-rate, but we wanted to integrate it more fully into a curriculum that would speak directly to the general ethos of Marshall College and its commitment to diversity and social justice.

Our committee (Michael Monteon from history, Amy Bridges from political science, and me) arrived at a three-quarter sequence we called “Diversity, Justice, and Imagination.” (Later it came to be called “Dimensions of Culture” – “DOC” – somewhat to my dismay.) We thought of the fall term on “diversity” as drawing particularly on sociology and anthropology as basic disciplines and providing a descriptive map of the different kinds of diversities around which U.S. society has been defined and often divided – racial, ethnic, gender, and religious diversities. “Justice” in the winter would look more historically at how the United States over time had developed political and legal resources for resolving disputes about diversity in ways that – on balance – advanced the cause of what one legal historian called “plural equality.” And the spring quarter on “Imagination” looked to the humanities rather than the social sciences and how our artists have imaginatively reflected on diversity and ideals to which the country at its best aspires – but has not reached.

As it developed, DOC was shaped more by its instructors than by the framework our committee provided, but to this day elements of that original skeleton can be found.

In 2001-03, I served as acting provost at Marshall. This was a privilege, enabling me to see a UCSD I barely knew. I learned to see the university from a student’s perspective, and I came to understand just how much students’ experience at UCSD is shaped by the extraordinarily dedicated and skilled staff they encounter in the colleges, from academic advising to student affairs to the residence halls.

I am thousands of miles away from UCSD now, having taken a full-time position at Columbia University’s Journalism School in 2009, but UCSD and in particular Thurgood Marshall College will always be in my heart. Happy birthday, TMC!

Dr. Michael Schudson was acting Provost of TMC from 2001-3, as well as instrumental in developing DOC and the Public Service Minor

I marvel at how my former years at Thurgood Marshall College (TMC) have enabled ordinary people to accomplish such extraordinary things. My journey at TMC had allowed me to be a part of the naming of our college, the creation of the Preuss and Gompers Charter Schools, the development of the Dimensions of Culture Program, the start of the African American Studies and Public Service Minors and the creation and enhancement of traditions such as Thurgood Marshall Week, Cultural Celebration and Marshall Palooza. I can clearly recall how some of these ideas were met with elements of resistance and how that pushback resulted in the pursuit of those ideas with more vigor and passion - all in the name of justice, access, awareness, opportunity, education, tradition and simply doing the right thing.

When fully embraced, our rich history inspires change and creates generations of change agents who find creative, relevant ways of responding to the needs of society. We have never been afraid of the challenge, only inspired to use our gifts to “be the change we wish to see in the world.” Exposure to our mission and academic /co-curricular programs have broadened perspectives, enhanced capacities to care and have inspired steps towards leaving our communities better than we found them. I have literally seen leaders emerge, paths changed and lives saved through the work we have done!

As Dean of Student Affairs, from 2000 to 2008, I had the honor of working with incredible, resilient students. They have enabled me to be both teacher and student, growing with and as a result of their discovery of self, talents and purpose. The caliber of our staff, faculty and administration has modeled the way by demonstrating sacrifice, commitment and excellence. I suspect that the impact of our mission, combined with the strength of our past and the potential we embody, will render the next 40 years as vibrant and rewarding as the first. As we continue to reflect on our past, it is my hope that the common thread of doing the right thing will lead us into our next 40 years of creation, action, social justice and our development as lifelong scholars and citizens!

Ashanti Hands was Dean of Student Affairs, 2000-2008

Professor Angela Davis’ teaching career has taken her to San Francisco State University, Mills College, and UC Berkeley. She also has taught at UCLA, Vassar, the Claremont Colleges, and Stanford University. She spent the last fifteen years at the University of California Santa Cruz where she is now Professor Emerita of History of Consciousness, an interdisciplinary Ph.D program, and of Feminist Studies.

Angela Davis is the author of eight books and has lectured throughout the United States as well as in Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and South America. In recent years a persistent theme of her work has been the range of social problems associated with incarceration and the generalized criminalization of those communities that are most affected by poverty and racial discrimination. She draws upon her own experiences in the early seventies as a person who spent eighteen months in jail and on trial, after being placed on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted List.” She has also conducted extensive research on numerous issues related to race, gender and imprisonment. Her most recent books are Abolition Democracy and Are Prisons Obsolete? about the abolition of the prison industrial complex, and a new edition of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. Angela Davis is a founding member Critical Resistance, a national organization dedicated to the dismantling of the prison industrial complex.

1) Your ties to UC San Diego can be traced to the philosopher Herbert Marcuse and your postgraduate studies under him at our campus in the late 1960s. Can you please reflect a little on that period of your life at UC San Diego and the initial seeds behind the creation of Third College/Thurgood Marshall College?

My first encounter with Herbert Marcuse was during my undergraduate years at Brandeis. Because I was interested in continental philosophy, he encouraged me to study in Frankfurt, Germany, where I would have an opportunity to attend lectures and seminars offered by his colleagues Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. I also attended lectures by Jürgen Habermas and other important Germany philosophers. After two years in Frankfurt, I decided to follow Marcuse, who had accepted a position at UCSD.

During the period I spent at UCSD, black and latino organizations – the Black Panther Party and the Brown Berets, for example – were visibly challenging racist institutions. We as black, Latino, and progressive white undergraduates, graduate students and faculty were inspired by the general climate of struggle to demand change on our campus. Eventually we decided to conduct a protracted struggle to name the third college (at the time Revelle and Muir were the only established colleges) after Patrice Lumumba and Emiliano Zapata. Our demands included new admission policies that would bring large numbers of black, Latino and working class white students to the university. If I remember correctly, we wanted the Lumumba Zapata College to consist of one-third black students, one-third Latinos and one-third working class white students.

2) In your PBS Frontline interview some years ago, you were asked about Marcuse's prophesy of a black bourgeoisie coming out of the 1960s civil rights movement. In your response you spoke about the lack of political connection between the black middle class and the increasing numbers of black people who are more impoverished. How do you see this equilibrium in the age of an Obama presidency?

Martin Luther King recognized toward the end of his life that civil rights alone would not solve the vast problems confronting black communities. The 1960s Civil Rights Movement was immensely important – especially considering the role it played in ending the vestiges of slavery that were inscribed in the law. But, as Dr. King acknowledged, voting rights and other civil rights, as important as they may have been, could not bring an end to racialized poverty nor could they solve the problem of institutionalized forms of racism in education, the prison system, etc.

Although there is much talk about the “post-racial” era of the Obama presidency, I think that racism is more dangerous today that during the period of the Civil Rights Movement. The most dramatic example of 21st century racism is the disproportionately large number of people of color in the country’s jails and prisons and the disproportionately small number of people of color –especially black men - in colleges and universities.

3) Van Jones was a keynote speaker on our campus last May and spoke about the twinning of two issues not normally linked together: greening the environment and the quality of life in the inner cities. Would you consider that a front page headline topic in 2011?

We know that poor people of color have suffered excessively from the pollution and destruction of the environment. The term environmental justice was designed to make the connection between racial justice and efforts to save the environment. In the 21st century, global capitalist clandestinely promotes racism, as it overtly promotes profits before the needs of people and before the protection of the environment. On the other hand, those of us who struggle for freedom need to expand our notion of what it means to be free: freedom does not only apply to human beings – of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, of all genders and sexualities, of all nationalities, and abilities, but also to nonhuman creatures and to the earth itself.

4) The UC Board of Regents in 1969 fired you from your teaching position at UCLA ostensibly due to your membership in the Communist Party and the American Association of University of Professors censured the Regents for this action. Subsequently you were rehired after a legal proceeding. How has the university climate in our country changed, if at all, in the span of forty years?

While it is difficult to compare the current period with the climate forty years ago, largely because this is not an era in which social movements can claim the kind influence they exerted then, I can say that even as the academy has appeared to become more open, the effect of the culture wars has been to infuse conservatism into many areas of university life. Today, for example, the newer, more interdisciplinary programs and departments are suffering as a result of the budget crisis. Faculty are still denied tenure because of their perceived political affiliations. The important political scientist Norman Finkelstein, who writes in the Israeli-Palestian conflict, has been locked out of the academy because of his critiques of Israel.

5) You're frequently on the national speaker series. When you give a keynote address, what is the thrust of your message today and what questions do your audiences ask?

I speak on a number of issues, but I am most interested in urging audiences to make connections between ideas and issues that are generally not linked together. Prison abolition and educational equality, for example. Global capitalism and U.S. racism; feminism and environmental justice; transgender rights and civil rights….

6) Our campus has an African American Studies Minor (AASM) which is relatively new and has great desire to grow. The symbolism of AASM is vital to UC San Diego. What is the intellectual and political formula to make the most of programs such as AASM and what are the considerable landmines in building such programs on a campus known for the sciences?

As African American Studies arose within a historical context of struggle for racial justice, I believe that it is important to maintain an explicit connection to the larger quest for social equality. The widely publicized events on the UCSD campus last year were a major reminder that individualized acts of racism are generally linked to larger structural issues. It is urgently important to support AASM, and at the same time to call for the admission of more black students and the hiring of more black faculty. These campaigns would be most effective when linked to demands for more Latina/o students and faculty and in general an increased presence of underrepresented groups.

7) If in certain quarters of America's political landscape you are greatly misunderstood, to put it mildly, how should young college students today understand your amazing life's trajectory?

Historical events are never understood by younger generations in the way the original participants experienced them. I have no problems with this necessary discrepancy. Moreover, I am, not too concerned about being remembered in a particular way. What I am concerned about, however, is that younger generations – especially college students – recognize the role mass movements have played in producing the history that is our present. In my case it would be important to remember that millions of people throughout the country and around the world participated in a global effort that effectively challenged the agenda of the U.S. government and the state of California. Both Richard Nixon as president and Ronald Reagan as California governor publicly identified themselves with the forces that supported my conviction and execution. But the people prevailed. Students today need to recognize that ordinary people, when they stand together, can bring about vast transformations.

A student-led reform movement at the UC San Diego, in which African American and Chicano/a students demanded access, curricular reform, and other substantial changes to the exclusionary policies of the elite La Jolla campus.

UCSD Lumumba-Zapata Movement 1969-1972 photo gallery »

The Preuss School, which began the UCSD Charter School Partnerships, is the brainchild of former TMC Provost Cecil Lytle.

Charter Schools: First Preuss and now Gompers? Host Jim Langley welcomes San Diego School Board President Luis Acle and UCSD's CREATE director Bud Mehan to explore UCSD's role in improving K-12 education with the campus-based charter Preuss School and UCSD's efforts in helping the Gompers Middle School in Southeast San Diego become a charter school in fall of 2005

Commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision that declared racially segregated schools unconstitutional, The Haunting of Jim Crow examines the events surrounding that momentous decision by weaving together the personal stories and reflections of two key protagonists, civil rights attorney (later Supreme Court Justice) Thurgood Marshall and segregationist Senator Strom Thurmond. The result is a multi-layered, multi-dimensional, and intensely personal interpretation of history. The play was written by UCSD Theatre professor and TMC Provost Allan Havis. [4/2005]

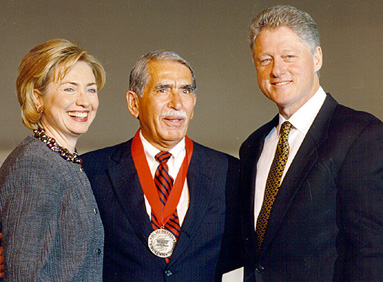

Dedication of Thurgood Marshall College, UC San Diego in 1993:

- 1 of 6: Dr William J McGill, UCSD Chancellor 1968-70 and

Dr Richard Atkinson, UCSD Chancellor - 2 of 6: Provost Cecil Lytle

- 3 of 6: Alumni Alex Wong, James Hill, Student Council Chair

- 4 of 6: Marian Wright Edelman, President Children's Defense Fund

- 5 of 6: Marian Wright Edelman (continued), Professor Carlos Blanco

– Lifetime Achievement Award presented by Provost Cecil Lytle - 6 of 6: Professor Carlos Blanco, UC President Jack Peltason